The Journalists’ Case: The Story of Four Reporters Convicted for Doing Their Job

The Journalists’ Case: The Story of Four Reporters Convicted for Doing Their Job

On April 15, the Nagatinsky District Court of Moscow sentenced Antonina Favorskaya, Sergey Karelin, Konstantin Gabov, and Artyom Kriger. The journalists were convicted under the charge of “participation in an extremist community” (Part 2, Article 282.1 of the Russian Criminal Code) and sentenced to five and a half years in a general regime penal colony.

Antonina Favorskaya was detained in March 2024 at the Borisovskoye cemetery, shortly after the burial of Alexei Navalny. After serving a 10-day administrative arrest for allegedly resisting the police, Favorskaya was re-arrested, this time as part of a criminal case. Soon after, on the same day—April 28—Kriger, Karelin, and Gabov were detained in different regions. All were charged under the same criminal case: participating in the activities of an extremist organization. The Russian state designated the Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) as such in 2021, and it was for creating FBK that Alexei Navalny was sentenced to 19 years in a high-security prison.

Each journalist was accused of cooperating with FBK in some form.

Let’s look at this story from three angles: Pro, Contra, In fact.

Contra

It was incredibly difficult to understand what exactly the journalists were accused of. The trial was held behind closed doors from the very beginning—meaning no friends, relatives, or press were allowed in the courtroom. The prosecution had petitioned for this secrecy, and Judge Borisenkova granted it at the first hearing in October last year. According to SOTA, the justification was a mysterious letter from the “E” Center (a division of Russia’s Interior Ministry for combating extremism), warning of alleged provocations planned by Navalny’s team. (A similar letter was cited as justification for closing the trials of Navalny’s lawyers Vadim Kobzev, Igor Sergunin, and Alexei Liptser.)

After her arrest, Favorskaya sent a letter to the SOTA editorial office summarizing her understanding of the charges:

“And now these clowns are charging me over my reports from Kovrov, Salekhard, and Moscow. Most cynically, they are ‘trying’ me (quote) ‘for helping to organize Alexei Navalny’s funeral.’ Only those who are deeply afraid and know only how to retaliate could reach such a level of surrealism.”

The only clear statement of the accusation comes from the official Telegram channel of the Moscow general jurisdiction courts:

“Collecting materials, producing and editing videos and publications for FBK.”

Pro

The same Telegram channel described the defendants as follows:

- Antonina Kravtsova (Favorskaya) – journalist at SOTA Vision

- Konstantin Gabov – producer for Reuters’ news service

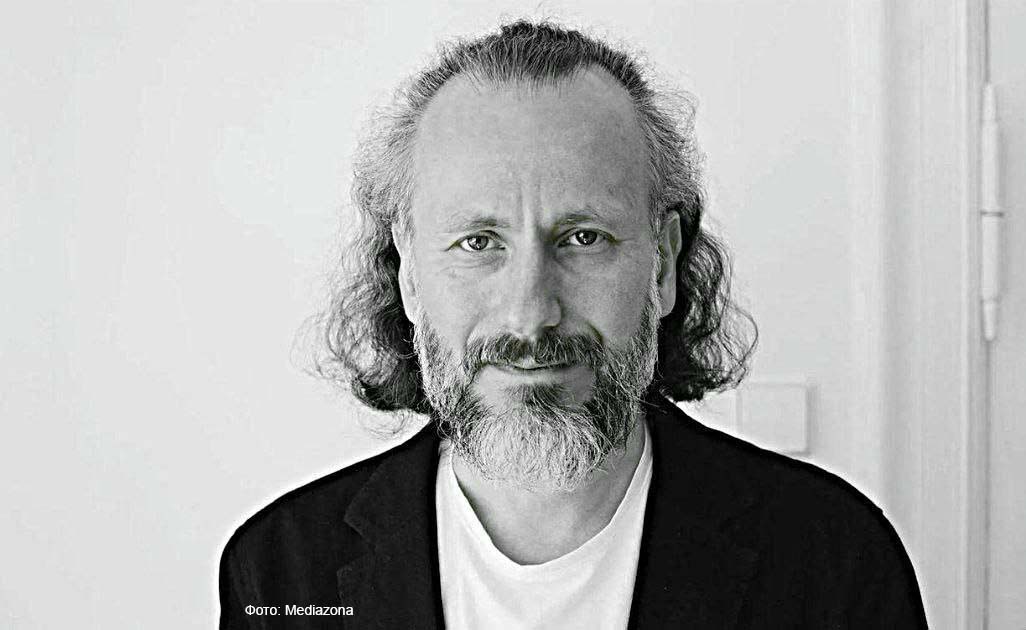

- Sergey Karelin – video journalist

- Artyom Kriger – journalist

None of the official court publications stated that any of the defendants were official or freelance FBK employees.

According to Favorskaya’s acquaintances, she worked solely as a reporter for SOTA, and all the materials she produced were intended for that outlet. Long before her arrest, she had privately expressed frustration that her content often spread to other platforms without proper attribution. One such example was her report from February 15, 2024, from the Vladimir City Court during one of Alexei Navalny’s lawsuits.

On February 15, 2024, SOTA Vision published video footage from what would be Navalny’s final court appearance.

The following day, after the news of Navalny’s death shocked the world, the video appeared on Dozhd, Ksenia Sobchak’s platforms, and many other news outlets

In Fact

The trial of the journalists was not just closed, but super-closed: we don’t know the full wording of the charges, the prosecutor’s arguments, or the defense’s rebuttals. There is no way to determine how the prosecution established that the journalists’ content was intended for FBK’s media platforms. All participants in the trial were bound by non-disclosure agreements.

In this section, we usually include the defendants’ final statements. But the closed trial format deprived them not only of a public hearing but also of the basic right to be heard after the verdict. No one heard what they said in court—but thanks to letters from pre-trial detention, we know what they intended to say.

Artyom Kriger:

“I am a true patriot of Russia. I want Russia not to be isolated, for us to be respected, not feared. I want freedom inside the country, so people like me can work in journalism without fearing for their freedom or lives. I support the rotation of power and separation of powers, so that we become a true democratic state—not a totalitarian one. Is that so hard to understand? If in 2025 I have to pay for these beliefs with my freedom, I am ready.”

The full version of Kriger’s final statement is available through SOTA Vision.

Sergey Karelin:

“Remorse is considered a mitigating factor. But remorse is for criminals. I am in prison for my professional activity, for honest and impartial journalism, for love—for my family and for my country.”

Konstantin Gabov:

“Even from behind bars, I believe we must speak from within Russia about Russia’s issues. Working under these extreme conditions is hard—but possible. What matters is that it’s necessary. We must show that there is another perspective in this country, that there are people worth talking to. Not everyone in Russia is blinded by propaganda. This matters both for the domestic audience and for the world.”

The final statements of Karelin and Gabov were published by Novaya Gazeta.

Antonina Favorskaya’s final statement could not be obtained—her letter was blocked by the Federal Penitentiary Service’s censorship.

This case vividly demonstrates that the Russian government will restrict freedom of speech by any means necessary. To close a trial, all it takes is a secret “letter from Center E” that no one but the judge and prosecution will ever see. And that’s enough to hand down a real prison sentence—without ever explaining what exactly the defendant did wrong.

P.S. Sever.Realii (a media outlet labeled as a “foreign agent”) analyzed Russian Supreme Court data and found that over the last ten years, the number of closed trials in Russia has doubled. In 2024, Russian courts held 25,683 trials behind closed doors—without press or public attendance. That’s twice as many as in 2015, when 12,226 cases were held in the same secretive manner.